Mekotio: These aren’t the security updates you’re looking for… | WeLiveSecurity

Another in our occasional series demystifying Latin American banking trojans

In this installment of our series, we introduce Mekotio, a Latin American banking trojan targeting mainly Brazil, Chile, Mexico, Spain, Peru and Portugal. The most notable feature of the newest variants of this malware family is using a SQL database as a C&C server.

As with many other Latin American banking trojans we have described earlier in this series, Mekotio has followed a rather chaotic development path, with its features being modified very often. Based on its internal versioning, we believe there are multiple variants being developed simultaneously. However, similar to Casbaneiro, these variants are practically impossible to separate from each other, so we will refer to them all as Mekotio.

Characteristics

Mekotio is a typical Latin American banking trojan that has been active since at least 2015. As such, it attacks by displaying fake pop-up windows to its victims, trying to entice them to divulge sensitive information. These windows are carefully designed to target Latin American banks and other financial institutions.

Mekotio collects the following information about its victims:

- Firewall configuration

- Whether the victim has administrative privileges

- Version of the installed Windows operating system

- Whether anti-fraud protection products (GAS Tecnologia Warsaw and IBM Trusteer[1]) are installed

- List of installed antimalware solutions

Mekotio ensures persistence either by using a Run key or creating an LNK file in the startup folder.

As is common for most Latin American banking trojans, Mekotio has several typical backdoor capabilities. It can take screenshots, manipulate windows, simulate mouse and keyboard actions, restart the machine, restrict access to various banking websites and update itself. Some variants are also able to steal bitcoins by replacing a bitcoin wallet in the clipboard and to exfiltrate credentials stored by the Google Chrome browser. Interestingly, one command is apparently intended to cripple the victim’s machine by trying to remove all files and folders in the C:Windows tree.

One way to identify Mekotio is a specific message box the trojan displays on several occasions (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Message box used by all Mekotio variants

(translation: “We are currently performing security updates on the site! Please, try again later! New security measures are being adopted: (1) new security plugin and (2) new visual look of the site. Your system will be restarted to complete the operation.”)

To ease stealing passwords with its keylogging feature, Mekotio disables the “AutoComplete” option in Internet Explorer. This feature, when enabled, saves time for Internet Explorer users by remembering inputs on various types of fields that have been filled in previously. Mekotio turns it off by changing the following Windows Registry values:

- HKCUSoftwareMicrosoftwindowsCurrentVersionExplorerAutoComplete

- AutoSuggest = “No”

- HKCUSoftwareMicrosoftInternet ExplorerMain

- Use FormSuggest = “No”

- FormSuggest Passwords = “No”

- FormSuggest PW Ask = “No”

For an in-depth analysis of one specific variant of Mekotio targeting Chile, refer to ESET’s recently published article (in Spanish).

We believe the main distribution method for Mekotio is spam (see Figure 3 for an example). Since 2018, we have observed 38 different distribution chains used by this family. Most of these chains consist of several stages and end up downloading a ZIP archive, as is typical for Latin American banking trojans. We dissect the two most commonly used chains in the following sections.

Figure 3. Example of a spam email distributing Mekotio

(Translation: “Dear citizen, Your requested receipt: … Download receipt”)

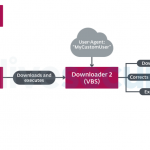

Chain 1: Passing context

The first chain consists of four consecutive stages, as illustrated in Figure 4. A simple BAT dropper drops a VBScript downloader and executes it using two command line parameters – a custom HTTP verb[2] (“111SA”), and a URL from which to download the next stage. The downloader downloads the next stage (yet another downloader) from the provided URL while using a custom User-Agent value (“MyCustomUser” and its variations). The third stage downloads a PowerShell script, correcting the URL from which to download Mekotio inside the script’s body, before executing it. The PowerShell script then downloads Mekotio from the corrected URL and installs and executes it (the execution process is described in detail later).

There are two interesting things about this chain. The first one is the usage of custom values for both User-Agent header and HTTP verb. These can be used to identify some of Mekotio’s network activity.

The other interesting aspect is the passing of context (either as command line arguments or by modifying the body of the next stage). This is a simple, yet effective, form of anti-analysis technique, because if you have Downloader 1 without the matching Dropper, you will have neither the URL nor the custom HTTP verb needed to obtain the next stage of the malware. Likewise, having Downloader 3 without Downloader 2 is useless, because the URL is missing. This approach makes analysis harder without the knowledge of context.

Chain 2: MSI with embedded JavaScript

As with many other Latin American banking trojans: Mekotio utilizes MSI in some of its latest distribution chains. In this case, the chain is much shorter and less robust, as only a single JavaScript, serving as the final stage, is embedded in the MSI and executed.

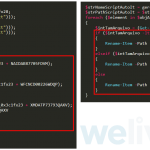

Compared to the PowerShell final stage from the previous chain, there are some visible similarities. The main one (shown in Figure 5) is the installation routine, called after downloading and extracting the ZIP archive, that renames the contents of the extracted ZIP archive according to file size. That is closely connected to the execution method described in the next section.

Figure 5. Comparison of installation routine in JavaScript and PowerShell scripts used by Mekotio, highlighting the similarity in basing the decision on file size

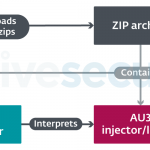

Execution by abusing AutoIt interpreter

Mekotio is most commonly executed by abusing the legitimate AutoIt interpreter. In this scenario, the ZIP archive contains (besides the Mekotio banking trojan) a legitimate AutoIt interpreter and a small AutoIt loader or injector script. The final stage of the distribution chain executes the AutoIt interpreter and passes the loader or injector script to it to interpret. That script then executes the banking trojan. Figure 6 illustrates the whole process.

Figure 6. The execution method most commonly used by Mekotio

Mekotio is not the only Latin American banking trojan using this method, but it favors it significantly more than its competitors.

Cryptography

The algorithm used to encrypt strings in Mekotio’s binaries is essentially the same one Casbaneiro uses. However, many variants of Mekotio modify how the data are processed before being decrypted. The first few bytes of the hardcoded decryption key may be ignored, as may some bytes of the encrypted string. Some variants further encode encrypted strings with base64. The specifics of these methods vary.

C&C server communication

SQL database as C&C server

Some variants of Mekotio base their network protocol on Delphi_Remote_Access_PC, as does Casbaneiro. When that is not the case, Mekotio utilizes a SQL database as a sort of C&C server. This technique is not unheard of in relation to Latin American banking trojans. Instead of a SELECT command, Mekotio seems to rely on executing SQL procedures. That way, it is not immediately clear what the underlying database looks like. However, the login string is still hardcoded in the binary.

C&C server address generation

We have observed three different algorithms for how Mekotio obtains the address of its C&C server. We describe them below in the chronological order that we encountered them.

Based on hardcoded lists of “fake domains”

The first method relies on two hardcoded lists of domains – one for generating the C&C domain and the other one for the port. A random domain is chosen from both lists and resolved. The IP address is further modified. When generating the C&C domain, a hardcoded number is subtracted from the last octet of the resolved IP address. When generating the C&C port, the octets are joined together and treated like a number. For clarity, we have implemented both algorithms in Python, as seen in Figure 7. Notice that this approach is surprisingly similar to the one used by Casbaneiro (marked as method 5 in the hyperlinked analysis).

|

def generate_domain(base_domains, num): domain = to_ip(random.choice(base_domains)) octets = domain.split(“.”) octets[3] = chr(int(octets[3]) – num) return octets.join(“.”) def generate_port(base_domains): domain = to_ip(random.choice(base_domains)) return int(domain.split(“.”).join(“”)) |

Figure 7. Code for generating C&C domain and port from hardcoded lists of domains

Based on current hour

The second approach utilizes a Domain Generation Algorithm (DGA) based on current local time (therefore, victim’s time zone affects the result). The algorithm takes the current day of the week, day of the month and hour and uses them to generate a single string. It then calculates the MD5 of that string, represented as a hexadecimal string. The result joined with a hardcoded suffix is the C&C server domain (its port is hardcoded in the binary). Figure 8 shows our Python implementation of this algorithm.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 |

day_names = { 0: “MON”, 1: “TUE”, 2: “WED”, 3: “THU”, 4: “FRI”, 5: “SAT”, 6: “SUN”, } hour_names = { 7: “AM02”, 8: “AM03”, 9: “AM04”, 10: “AM05”, 11: “AM06”, 12: “PM01”, 13: “PM02”, 14: “PM03”, 15: “PM04”, 16: “PM05”, 17: “PM06” } def get_hour_name(hour): if hour <= 6 or hour >= 18: return “AM01” else return hour_names[hour] def generate_domain(suffix): time = get_current_time() dga_data = “%s%02d%s” % (day_names[time.dayOfWeek], time.day, hour_names[time.hour]) dga_data = hexlify(md5(dga_data)) return dga_data.lower() + suffix |

Figure 8. Code for generating C&C domain based on current hour

Based on current day

The third algorithm is somewhat similar to the second one. It differs in the format of the string created from local time and the fact that it uses a different suffix each day. Additionally, it generates the C&C port in a similar manner. Once again, the Python re-implementation of the code is illustrated in Figure 9.

|

def generate_domain(domains_list, subdomain): time = get_current_time() dga_data = “%02d%02d%s” % (time.day, time.month, subdomain) dga_data = hexlify(md5(dga_data)) return dga_data[:20] + “.” + domains_list[time.day – 1] def generate_port(portstring): time = get_current_time() return int(“%d%02d%d” % (time.day, time.dayOfWeek, time.month)) |

Figure 9. Code for generating C&C domain and port based on current day

Multiple concurrent variants?

We already mentioned that, similar to other Latin American banking trojans, Mekotio follows a rather chaotic development cycle. However, besides that, there are indicators that there are multiple variants of Mekotio being developed simultaneously.

The two main indicators are internal versioning and the format of the string used for exfiltrating information about the victim’s machine collected by Mekotio. We have identified four different versioning schemes:

- Numbering (001, 002, 072, 39A, …)

- Version by date (01-07, 15-06, 17-10, 20-09, …)

- Version by full date (02_03_20, 13_03_20, 26_05_20, …)

- Numbering and date combined (103–30-09, 279–07-05, 293–25-05, …)

Each of these schemes is associated with a specific format of the exfiltrated data string. Since we see multiple of these schemes simultaneously, we believe that there may be multiple threat actors using different variants of Mekotio.

Conclusion

In this blog post, we have analyzed Mekotio, a Latin American banking trojan active since at least 2015. As in the other banking trojans described in this series, Mekotio shares common characteristics for this type of malware, such as being written in Delphi, using fake pop-up windows, containing backdoor functionality and targeting Spanish- and Portuguese-speaking countries.

We have focused on the most interesting features of this banking trojan, such as its primary method of execution by abusing the legitimate AutoIt interpreter, using SQL database as a C&C server or the different methods Mekotio uses to generate the address of its C&C server.

We have also mentioned several features that are surprisingly similar to Casbaneiro.

For any inquiries, contact us at [email protected]. Indicators of Compromise can also be found in our GitHub repository.

Indicators of Compromise (IoCs)

Hashes

Mekotio samples

| SHA-1 | Description | ESET detection name |

|---|---|---|

| AEA1FD2062CD6E1C0430CA36967D359F922A2EC3 | Mekotio banking trojan (SQL variant) | Win32/Spy.Mekotio.CQ |

| 8CBD4BE36646E98C9D8C18DA954942620E515F32 | Mekotio banking trojan | Win32/Spy.Mekotio.O |

| 297C2EDE67AE6F4C27858DCB0E84C495A57A7677 | Mekotio banking trojan | Win32/Spy.Mekotio.DD |

| 511C7CFC2B942ED9FD7F99E309A81CEBD1228B50 | Mekotio banking trojan | Win32/Spy.Mekotio.T |

| 47C3C058B651A04CA7C0FF54F883A05E2A3D0B90 | Mekotio banking trojan | Win32/Spy.Mekotio.CD |

Legitimate AutoIt interpreter being abused

| SHA-1 | Description | ESET detection name |

|---|---|---|

| ACC07666F4C1D4461D3E1C263CF6A194A8DD1544 | AutoIt v3 Script interpreter | clean |

Network communication

- User-Agent: “MyCustomUser”, “4M5yC6u4stom5U8se3r” (and other variations)

- HTTP verb: “111SA”

Bitcoin wallets

- 1PkVmYNiT6mobnDgq8M6YLXWqFraW2jdAk

- 159cFxcSSpup2D4NSZiuBXgsGfgxWCHppv

- 1H35EiMsXDeDJif2fTC98i81n4JBVFfru6

MITRE ATT&CK techniques

Note: This table was built using version 7 of the MITRE ATT&CK framework.

| Tactic | ID | Name | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Initial Access | T1566.002 | Phishing: Spearphishing Link | Mekotio distribution chains start with a malicious link in an email. |

| Execution | T1059 | Command and Scripting Interpreter | Mekotio is most commonly executed by abusing the legitimate AutoIt interpreter. |

| T1059.001 | Command and Scripting Interpreter: PowerShell | Mekotio uses PowerShell to execute its distribution chain stages. | |

| T1059.005 | Command and Scripting Interpreter: Visual Basic | Mekotio uses VBScript to execute its distribution chain stages. | |

| Persistence | T1547.001 | Boot or Logon Autostart Execution: Registry Run Keys / Startup Folder | Mekotio ensures persistence by using a Run key or creating a LNK file in the startup folder. |

| Defense Evasion | T1218 | Signed Binary Proxy Execution | Mekotio is executed by running a legitimate AutoIt interpreter and passing a loader script for it to interpret. |

| Credential Access | T1555.003 | Credentials from Password Stores: Credentials from Web Browsers | Mekotio steals credentials from the Google Chrome browser. |

| Discovery | T1010 | Application Window Discovery | Mekotio discovers various security tools and banking applications based on window names. |

| T1083 | File and Directory Discovery | Mekotio discovers banking protection software based on file system paths. | |

| T1518.001 | Software Discovery: Security Software Discovery | Mekotio detects the presence of banking protection products. | |

| T1082 | System Information Discovery | Mekotio collects information about the victim’s machine, such as firewall status and Windows version. | |

| Collection | T1056.001 | Input Capture: Keylogging | Mekotio is capable of capturing keystrokes. |

| Command and Control | T1568.002 | Dynamic Resolution: Domain Generation Algorithms | Mekotio generates its C&C domain using a DGA. |

| T1568.003 | Dynamic Resolution: DNS Calculation | Mekotio uses an algorithm to modify the resolved IP address to obtain the actual C&C address. | |

| T1095 | Non-Application Layer Protocol | Mekotio’s network protocol in variants not using SQL is based on Remote_Delphi_Access_PC. | |

| Exfiltration | T1041 | Exfiltration Over C2 Channel | Mekotio sends the data it retrieves to its C&C server. |

[1] Anti-fraud solutions used very frequently in Latin America.

[2] Common HTTP verbs are GET and POST.